Edito

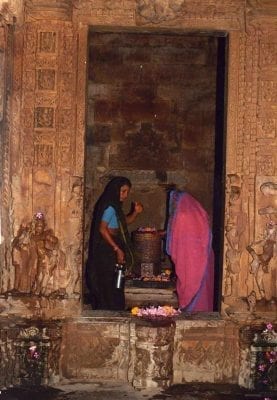

Puja performed by two women before the lingam at the Duladeo temple, Khajuraho, (2000).

Puja performed by two women before the lingam at the Duladeo temple, Khajuraho, (2000).

We felt we should illustrate this letter with a Lingam, since – being devoted to Alain Daniélou, who concerted to Shaivite Hinduism – it was his wish to use this sort of image on the cover of many of his works as an alternative to the ithyphallic image of the God in the famous sculpture on the pediment of the mediaeval temple at Bhuvaneshvar in Orissa. We must refer to what the great Leonardo da Vinci wrote:

Della Verga [On the Member]

Della Verga… e pare che a torto l’omo si vergogni di nominarlo, non che di mostrarlo, anzi sempre lo copre e lo nasconde, il qual si dovrebbe ornare e mostrare con solennità come ministro. Dell’Anatomia, fogli B, pubblicati da Teodoro Sebachnikoff, Roux e Viarengo, Torino 1901, p.84. (An. B; 13 r.)

[and it seems that wrongly man is ashamed to name it, as well as to show it, and rather always

covers and hides it, which he should adorn and show solemnly, as its minister]

In our own prudish times – even modern India has been struck by this disease, despite being the home of the Kama Sutra and erotic temple sculptures – Alain Daniélou was never afraid to wear over his elegant plaid ties a small gold phallus, an emblem of the Shiva cult he professed. For most Hindus, the lingam is principally associated with the god’s sexual organ, although it may also have other forms. At Varanasi, the city of Shiva, the souvenir stalls overflow with every type and size of lingam.

On this subject, Alain Daniélou wrote;

Abstracts from the Introduction to Mystère du culte du linga

Pages 69 to 71:

Lingam actually means ‘sign’. Grammatically, it indicates the masculine as compared to the

feminine. It is what distinguishes the masculine, probably from the very beginning. It is a word that serves in all sorts of ways.

A symbol is an attempt to portray, to evoke an abstract principle through a concrete image. All religions, all metaphysics are inevitably expressed by symbols. For this reason, I felt it useful to give an explanation in interpreting a special symbol, the Lingam or phallus, worshipped by all Hindus.

This text is useful in that it presents the traditional approach to a symbol such as the phallus, an important approach owing to its freedom of thought in the context of the Anglo-Saxon Puritanism that has invaded modern India.

Abstracts from the Introduction to Signification de le Grande Déesse. Page 122:

The gods are not inventions; they are forms that one chooses out of an informal multiplicity. Curiously, it is the monotheists who create completely different forms of the entities they worship, whereas in the end polytheism blends in a multiple unity that by its very nature is unknowable.

This is what the late Jean Varenne, one of the most eminent French Sanskritists, wrote in June 1994 in “Connaissance des Religions” on the subject of Alain Daniélou’s published translation of three texts by Swami Karpātri:

The recent death of Alain Daniélou deprives those interested in Hindu tradition of a direct approach of teaching given, in our own times, in those circles where young Brahmins are taught the basics of their religious culture. Indeed, as a rule, the works available in the West have either been written by authors outside Hinduism (and sometimes outside all religion), or by highly westernized masters whose neo- spiritualism has a very meagre audience in India, but all the same attract students from Europe or America, whose main characteristic is – unfortunately – their disconcerting naivety, resulting from a distressing ignorance of their own traditions. Happily, there are exceptions, as the work of Alain Daniélou bears witness. When, during the ’thirties, he decided to move to India, he chose Benares, which brought him into contact with people for whom Hinduism was a living reality. Thus he made the effort to learn Hindi and listened to those who perpetuated Brahmanic teaching in the hostile environment of the Kali-Yuga. His decisive meeting was with Swami Karpātri (1907-1982), a Brahmin who had become a “renouncer” (sannyāsin or sādhu) in the Vedantic Sarasvatī tradition, one of the most orthodox. Having become his pupil and later friend, Alain Daniélou was finally able to accomplish his mission: to reveal to the West that Hindu tradition is not dead, but survives despite contrary winds and tides in discreet lodges scattered throughout India and bound to each other by a whole network of “spiritual paths” trodden by those wandering monks who are the life-blood of Brahmanic orthodoxy.

….

Thanks to Alain Daniélou’s translation, we can see the concrete working of Brahmanic thought and how its essential content is transmitted in our own days (albeit sadly in increasingly restricted circles) just as it was at the time of the Upanishads.

Karpātri, as seen by Alain Daniélou – Deference, Respect, Praise

In his abundant archives, Alain Daniélou left many references to Swami Karpātri, in books, articles and interviews.

Not a single text, not one line or word but shows respect and admiration for this wandering monk, the spiritual head of Northern India, celebrated for his immense knowledge and wisdom.

The Daniélou Centre deems it useful to draw the attention of English speakers to the texts showing Alain Daniélou’s devotion to Swami Karpātri, and particularly to an interview in the book – no longer available – published only in French by Le Relié in 1993, containing Alain Daniélou’s translation of three texts by Karpātri.

It is important to note that Daniélou never took any interest, participated or wrote anything concerning the political aspects of Karpātri’s actions and was only interested in the latter’s philosophical and religious arguments. The Daniélou Centre wishes to continue that same approach and is scrupulous in never interfering in or publishing texts relating to Indian politics, which are none of its concern.

This is why the 2007 French edition of the book “Approche de l’Hindouisme”, containing texts that do not comply with our aims, has been withdrawn from sale. The 2005 edition is the sole valid text.

As far as political aspects are concerned, Daniélou cites Swami Karpātri only once, in 6 lines, in his “Brief History of India” (page 315) and not much more in his autobiography. Unfortunately, in both, he confuses two political movements. One of our last newsletters was referring to this confusion.

On page 152 of his autobiography, he wrote, “Swami Karpātri advised me to return to Europe and try to educate people on the basic principles of Hinduism; being a foreigner, I could not take part in the political struggle of India”.

Excerpts from Alain Daniélou’s writings concerning Swami Karpātri in the interview, granted one or two years prior to Alain Daniélou’s death (1992?), in the form of a preface to the book, published only in French by Editions du Relié, Robion, 1993:

“Textes fondamentaux de Swami Karpātri, Mythologie, Théologie et Philosophie, Traduits du hindi et commentés par Alain Daniélou”

1 Le Mystère du Culte du Linga

2 La signification de la Grande Déesse

3 L’Ame et le Moi.

Was Pandit Vijayananda a disciple of Swami Karpātri’s?

In a certain way, yes. He considered that Swami Karpātri had higher knowledge, so of course he would go and attend some of his audiences.

As the pupil of a famous sannyāsin Tantric Guru, Vijayananda too had a very wide experience and an entirely open mind, whereas I knew many Brahmans who were narrow-minded, carping and brought nothing profound to the study of the texts.

Swami Karpātri himself was a wandering monk, a sannyāsin, with incredible learning. He used to come to Benares from time to time, during the rainy season.

…………

When you met Swami Karpātri, did you immediately consider him a spiritual master?

For me, Karpātri belonged to a group of people who appeared to illuminate the world and from whom one could learn important things. But you don’t seek to become a disciple and they are not seeking to become gurus. Such a relationship is entirely unrealistic. I was merely in contact with several great Brahmans, and in particular Vijayananda Tripathi with whom I had some long conversations, and others with whom I was studying Sanskrit.

Like many others, I used to visit Karpātri when he was there, and he kindly answered a number of my questions. I was not looking for a guru however and he was not looking for disciples! That creates another atmosphere, another environment: the idea of seeking a guru is a wholly Western disease.

All those people who want to have a master and even become gurus themselves!

The question is this: does the Sanātana Dharma exist? Is there a tradition of knowledge and culture that gives value to the transmission of Hinduism? If it exists, it is something permanent and impersonal. So you approach that knowledge, more or less; you don’t approach people: you are not looking for a master, you are simply approaching a light.

However, you used to go and ask Swami Karpātri questions because for you he was a witness to reality.

Of course! He represented tradition. His knowledge was extraordinary, which is something one feels. What I mean is that some of the other sannyāsins in the same group did not have this same light; at

the same time, there were people who had that kind of luminous knowledge, of whom he is an exceptional example, which one feels at once.

Were the questions you asked him related to your meetings with Pandit Vijayananda and the work that derived from it?

No, they were simply questions that anyone might ask. There are not many people who can explain to you the various aspects of the Goddess, or the meaning of the Lingam, and do so in such an intelligent and realistic manner, without any kind of prejudice.

But they weren’t questions of a purely intellectual order, I suppose?

They weren’t purely intellectual because I had a profound respect and a kind of devotion toward this person, which created a sort of bond

Intellectual: what does that mean?

……….

Karpātri was very active, since he had created traditionalist movements around himself, which still play a major role in Indian politics. I was clearly not interested in the political aspect.

Although his activity was on a global level, you nevertheless underwent initiation.

In actual fact, I wasn’t even aware of it when I was in some kind of way adopted by Karpātri. It was so much beyond me that I didn’t understand that that little ceremony was an adoption rite. He took a Mala, a rosary of rudraksha seeds, with which he touched every part of my body, then he placed it around my neck: the gift of a Mala is an adoption rite. On my side, I thought him very kind to give me a Mala. It was only later that I realised it was a ritual act.

At that moment too, he told me I could translate and utilise – as I pleased – his teachings, his work, and even adapt them; that means that he was incorporating me into the tradition, since I was entitled to speak of them as though they were my own thought. It was a mark of trust that I was not expecting.

I suppose it was very exceptional to be recruited like that, as a non-Hindu.

There is no other case. Perhaps Sir John Woodroffe. …………

Could we say that Swami Karpātri was the source of your knowledge of Indian tradition?

No, I should say rather Pandit Vijayananda from the point of view of general knowledge. He himself was a highly revered Brahman, and you could discuss anything with him.

Swami Karpātri was on a higher level, like some kind of oracle you come to worship and put questions to. The relationship was not at all the same.

When he gave an audience, a darshana, seated on a low table like an Indian Yogi, there were always a lot of people, different groups: Brahmans, non-Brahmans, women: it was arranged like a theatre.

…………

So the devotional side was not part of his teaching?

Absolutely not! It’s far from being ‘churchy’! It’s very strict teaching, covering philosophy, knowledge …

It was very difficult to find out anything about his life apart from what he showed us. Some people claimed he practiced Tantrism, but I know nothing about it.

And then, that is part of his sādhana, those techniques you select for your personal development. That is not my business.

He didn’t teach these techniques?

No, absolutely not!

Had he got any disciples?

No, all India was his disciple.

A lot of people came to his darshanas to prostrate themselves before him, or listen to his teachings, when he gave any.

……….

Was Swami Karpātri integrated into Brahmanism; was he listened to?

Of course! He was considered a great scholar and a sort of saint, respected by everyone. He was in actual fact deemed to be the spiritual head of much of Northern India.

What were his duties in India at that time?

He had no duties. ……

Swami Karpātri took an interest in social matters. One might think that it doesn’t concern a renouncer. Isn’t that absolutely exceptional and surprising?

Taking the battlefield is envisaged in exceptional situations, when tradition is seriously threatened. He deemed it his duty to take action to stop the anti-traditionalism of the public authorities.

……

It is also for that reason that I published the Kāma-Sūtra: the sources of the Kāma-Sūtra have the same authors as some of the Upanishads; the commentary on the Kāma-Sūtra is contemporary to Shankarācharya. It seems to be very difficult for Indians to leave behind that puritan moralism they have adopted; they really believe that you can lead an ideal life with that kind of restriction.

…..

I believe that the young Brahman who worked with us and who himself became a very strict and puritanical sannyāsin of the Vedic kind left Karpātri because he claimed he practiced Tantrism. Yet Tantrism is part of tradition!

………..

In your work, you refer to ancient Shaivism as being the Primordial Tradition, the Sanātana Dharma. Can we say that Swami Karpātri, himself within Brahmanism, was one of the poles of ancient Shaivism?

No, because his political activities, on the contrary, were very Vedic. Shaivism is a form within Hinduism; whereas external religion is Vedic, Shaivism is its esoteric side. All sannyāsin sects are Shaivite. There are also Vishnuite sādhus, but they are not custodians of secret tradition. At the same time, all the Upanishads are basically Shaivite.

Do you mean that Swami Karpātri was a custodian of esoteric knowledge?

Certainly, at the highest level!

If ancient Shaivism is the esoteric aspect of Hinduism, does that mean it is always present, while remaining hidden?

Of course! And it must remain hidden. ………

Yet Swami Karpātri teaches about this knowledge and incarnates this knowledge

He is a person with knowledge, who knows all the texts, has a prodigious memory; he knows the meaning of all aspects of symbolism and mythology.

At the same time, it is possible for someone like Swami Karpātri to acquire certain powers so that he can surpass his intellectual potential, but it requires a special discipline that cannot be practiced by just anybody.

Can you tell us about Swami Karpātri’s teaching methods?

I am very much against rituals and I have never received special instruction. Our contacts were on a strictly intellectual plane. There was some physical veneration of the person: I prostrated myself before him like everyone else, but there was nothing special about my case.

The relationship between master and disciple is described as the locus where teaching is put into practice. Have you never felt anything of that kind?

No. Why do people look for a master? So as to play a role themselves! Now, I did not desire to play any role. So things were on another level. Karpātri certainly thought that I could be useful and so he did his best to make things easy for me.

There is however one curious point: after my adoption rite, which I didn’t take seriously, I had the impression of knowing things I had never learned.

At that moment, you probably belong to…, you are integrated into a certain tradition. How it is done, how it happened, has no importance.

I was not seeking a role however! I had the chance of being in contact with a certain kind of knowledge and I have tried to give expression to it. But I am not playing a role; I am not a guru!

News

An unauthorised edition of “Approche de l’Hindouisme” dated 2007, not complying with the policy of the Alain Daniélou Study Centre, has been withdrawn from sale and the only remaining reference is the original version published in 2005.

An unauthorised edition of “Approche de l’Hindouisme” dated 2007, not complying with the policy of the Alain Daniélou Study Centre, has been withdrawn from sale and the only remaining reference is the original version published in 2005.

Friends of Indian Music,

It is my pleasure to introduce you the activities of the CRN Production – a Centre for Performing Arts in Jodhpur (Rajasthan), a new creative space open to Artists from all over the world to perform, teach, exchange ideas and intercultural experiences.

See: www.crnproductions.com

On the footsteps of Alain Danielou, we have organized for this summer a special workshop of Indian music, with the

legendary dhrupad musician Ustad Rahim Fahimuddin Dagar:

Ustad Rahim Fahimuddin Dagar, is one of the living treasures (Padmabhushan) of the Indian classical music. Born in 1927 in the court of Alwar (Rajasthan) where is was the court musician, the Maestro is the 19th generation of uninterrupted lineage of musicians. For this reason his music is considered a pure example of the

past tradition, with rich repertoire of composition and vocal techniques that refers to nada Yoga (yoga of sound)

This workshop is open to all who want to experience the teaching of this great Maestro of the ancient art of Dhrupad, and to all singers, musicians and yoga practitioners who are interested in developing the relationship between body, breath (prana) and sound.

It is a very rare chance to learn from such a legendary artist, in the peaceful surroundings of old Rajasthani architecture where dhrupad was traditionally performed.

From the 22nd to the 29th August

http://www.crnproductions.com/workshops/1_dhrupad.html

The workshops will be held in Sukh Sagar Haveli, a peaceful space where the musicians would have performed in the 19th century. We would like to give the participants an idea of what it would have felt like to perform this traditional music in its purest and most original form, as it would have sounded like in the times when this music flourished.

No previous training in Indian music is required.

Dr. Cassio will facilitate the classes with extra sessions for beginners, teaching about historical and musicological aspects of Indian Music.

The classes will be in Hindi and English.

The workshop includes daily practice of rhythmic patterns (tala) with a percussionist (pakhawaj player)

Workshops schedule:

from 10 am to 1 pm : Vocal Classes

from 1 pm to 2 pm : Lunch

from 2:30pm to 4:30pm : Practice with percussion and extra classes with Dr. Cassio for beginners

For students that would like to participate in yoga, class timings will be 8:00am to 9:00am, after yoga breakfast will be served.

If you are interested in our activities, please register at the page SIGN UP !

Best Regards,

Francesca Cassio

Music and Mangement Director, CRN Productions www.crnproductions.com

Music

New Indian publication of the Tagore 18 songs-poems.

Published and endorsed by Visva Bharati (Santiniketan)

Manufactured and distributed by Questz World, the Music Company of the Rozaleenda Group, Inc (Kolkata, questz@questz.com)

YOUTUBE LINK :

Western fusion Rabindra Sangeet

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MyEIHFWICtk

Tagore’s Songs of Love and Destiny

Translated and specially transcribed for voice and piano by Alain Danielou (1907 – 1986) Presented by Francesca Cassio (vocalist) and Maestro Ugo Bonessi (piano)

“Songs and Poetries of Rabindranath Tagore in the Transcription of Prof. Alain Danielou for Voice and Piano”

Performed by Francesca Cassio and Ugo Bonessi

As Professor Alain Danielou writes in his biography, Tagore requested him to transcribe some songs from the Rabindra Sangeet according to the western vogue of the time, for voice and piano. It was infact The Poet’s wish that some of his songs could be sung also in the West. It was an innovative concept that Tagore himself wanted to promote, and that up nowdays nobody has yet performed in this form. Alain Danielou worked over 50 years on this project. He translated into english and transcribed for piano only 18 songs, in a way that the original melodies -with their embellishments and peculiar raga movements- could be recognized, but with a piano harmonic accompaniment that could support and emphasize the meaning of the poetries. The work of Danielou shines mostly in the elegant piano arrangement, and in the beautiful translation into english (and french) that match with the melodies as well as with the meaning. The blending of the musical Indian language with the western notation, and harmony, requires skills in both discipline, and for this reason for long time these song have never been performed. Due a professional training in both Classical Western and Hindusthani vocal music, in 2007 Dr. Francesca Casio and Maestro Ugo Bonessi have been in charge on the behalf of the Danielou Foundation to perform and record -for the first time- the cycle of the 18 songs of Tagore transcribed by Alain Danielou.