“New: Set up, on our Internet site, a debate forum in which you can exchange ideas on matters concerning the life and work of Alain Daniélou: music, India, history and society, philosophy and religion. You are cordially invited to take part…”

ACTUALITÉS

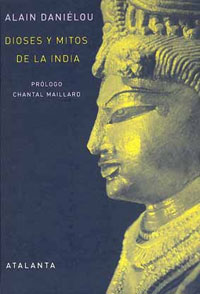

– Edition en langue espagnole de « Mythes et Dieux de l’Inde, le Polythéisme Hindou » aux Editions Atalanta, Girona.

DIOSES Y MITOS DE LA INDIA

DIOSES Y MITOS DE LA INDIA

ATALANTA

Prologo: Chantal Maillard

Traduccion: Antonio Rodriguez

This Study of Hindu mythology explores the significance of the most prominent Hindu deities as they are envisioned by the Hindus themselves. Referred to by its adherents as the “eternal religion”, Hinduism recognizes for each age and each country a new form of revelation – and for each person, according to his or her stage of development, a different path of realization. This message of tolerance and adaptability, the very heart of Hindu polytheism, resounds clearly throughout Alain Danielou’s work. Thirty-three photographic plates by Raymond Burnier further illustrate the many facets of Hindu teaching and trace the significance of the Gods of the Vedas, as well as Vishnu, Siva, Linga, Brahma, Kali, Sakti, and many other deities.

Article – India Blooms

By Brenda Dasgupta

Light of the Ganga:

Trans World Features

A recent exhibition of photographs by two Europeans who travelled by road all the way to India in the 1930s introduced viewers to a page from cultural interchange in pre- Independence India. Brinda Dasgupta reports

A recent exhibition of photographs by two Europeans who travelled by road all the way to India in the 1930s introduced viewers to a page from cultural interchange in pre- Independence India. Brinda Dasgupta reports

India has fascinated the West for centuries. While Albert Einstein credited the country for having taught the rest of the world to count, Mark Twain thought it to be “the cradle of the human race, the birthplace of human speech, the mother of history, the grandmother of legend, and the great-grandmother of tradition.”

Little wonder then that, way back in 1932, Frenchman Alain Danielou and his Swiss partner Raymond Burnier drove through Afghanistan to India on a discovery trail. Later, India was to become their home as both immersed themselves in the culture and literature of the land. Their travels and dedication to the country were chronicled in Lights of the Ganga , a photography exhibition, recently held at the Rabindranath Tagore Centre (Indian Council for Cultural Relations) in Kolkata.

Danielou and Burnier lived in Varanasi, the town that Twain described as being “older than history, older than tradition, older even than legend.” There they rented an old palace, Rewa Kothi, on the Assi Ghat. With the help of Indian pundits, Danielou began studying Sanskrit, Hindi, religious text and philosophy.

Danielou’s and Burnier’s photographs capture the old-world charm of Varanasi –the temples, the masseurs, the street scenes on the bank of the Ganga. These are remarkable for their artistic quality and the black & white tone stand out to define the culture and aestheticism that mark this ancient town. Some of the portraits are very rare, including the one of a young Pandit Ravi Shankar playing the Esraj.

While Burnier generally used a Leica, Danielou preferred a Rolleiflex. Even their style and subject matters were different. Burnier photographed monuments, temples and sculptures, while Danielou was more concerned with local scenes and the local population, particularly dancers, musicians, and their instruments. Between them, they created a repertoire of photographs of motifs, sculptures, figures, and structures that is exhaustive in its vastness and stunning in its style.

The duo’s travels were not confined to Varanasi, however. Says Reba Som, director, Rabindranath Tagore Centre, “Many are not aware that Danielou and Burnier were received warmly at Santiniketan by Tagore himself and that a deep friendship of sorts developed. In many ways, it was a meeting of minds, especially between Danielou and Tagore.”

Danielou had translated 18 of Tagore’s songs into English and French, and the two of them were to find in each other a spirit of kinship. Tagore trusted Danielou for his unconventional and free spirit, and Danielou appreciated the poet’s quick eye that detected and encouraged young talent.

Burnier passed away in 1968, and Danielou in 1994. Nevertheless, their legacy lives on, in the form of these photographs, and in the form of various books and records. Their constant reaching out to Indian culture, along with their staunch disapproval of the racial segregation imposed on India during the colonial rule, perhaps leads us to believe that not only were they questioning their own culture and rediscovering another in the process, but they were also giving voice and expression to the same.

It was also clear from the exhibition and other records that music was the food of love for Danielou. Says Som, “Danielou was a great musician, and in fact, Tagore had asked Danielou to head the music department at Visva Bharati, an offer that the Frenchman refused. He felt that musicians carry culture and civilization in their most essential and refined form, while helping to promote diversity and universality.”

Danielou’s passion for music led him to master the rudra veena, under the tutelage of Sivendranath Basu. Later, he went on to translate Sanskrit texts on the theory of music and studied the oral tradition of the Santhals, the Carnatic musical system, and the vocal tradition of the Dhrupad.

Danielou’s constant thirst for knowledge, and his irreverent attitude towards established schools of thought, earned him the reputation of a great philosopher and Sanskrit scholar.

The photographs were also displayed at Kala Bhavan in Varanasi, and the exhibits will go to Dhaka, Chittagong, and Delhi next.

– In view of the republishing of Alain Daniélou’s Le symbole du Phallus , for which the publisher’s choice of illustrations in the original French version (1993) did not please the author at all, Jacques Cloarec has just returned from a tour in Asia to complete the book’s iconography.

Thus, in Japan, he photographed a Shinto ritual and a procession in the town of Kawasaki, a Shinto temple containing phallic sculptures at the port of Ujahima at the very end of the Shikoku island and, at Bangkok, a small oratory to fertility, with its collection of phallus of all sizes and colours.

Blessing of the phalluses before the start of the procession.

Blessing of the phalluses before the start of the procession.

Festival participants.

Festival participants.

Procession of the heavy phalluses borne on palanquins.

Procession of the heavy phalluses borne on palanquins. The temple court.

The temple court.GALERIE

Photo : Alain Daniélou, 1938.

Photo : Alain Daniélou, 1938.

Raymond Burnier devant un paysage du Cachemire, 1938.

RÉTROSPECTIVE

Shiva and Dionysus.

The Omnipresent Gods of transcendence and Ecstasy

Inner Tradition International, Rochester, U.S.A.

Shiva and Dionysos are both guarantors of values whose common trait is that they belong outside or are against the laws of the city: nomadism, renunciation, the calling in question of social structures and hierarchies. Friends of the poor, of artists and vagabonds, they attract the suspicion or mistrust of representatives of the established order. Through these two figures with their undeniable similarities, Daniélou explores not only the domain of religion, but also – which is inevitable in dealing with Hinduism – those of society, culture, history and art. Drawing on sources whose extreme variety highlights their value, he shows how Shivaism has left its sign on Asiatic and European civilisations up to the far west since the Iron Age – an Age ironically named, since most of its artistic creations were made of perishable materials such as wood, traces of which are extremely rare. This is why the mark left by Shivaism is not obvious and can be apprehended only when seen from a Hindu and not from an exclusively western point of view. The testimony of ancient authors, monuments (megaliths, for example), the Upanishads and Purānas – the Sanskrit texts that hand down the teachings of Shivaism -, contemporary authors, whether Anglo- Saxon, Indian or French, all provide material on which the author draws in order to demonstrate this relationship in various civilisations.

This work has to fight a second preconception, that of Hinduism as a rigid and petrified society, with its hierarchical and ordered castes, but this means ignoring the presence of Shivaism, which is earlier than Hinduism. Daniélou explains that since the Aryan colonisation, two perfectly opposite tendencies have co-existed in India: Vedism, with its written tradition founded on the Vedas, which provided the structure of Hindu society and represents the sedentary and ordered way of living, and Shivaism, earlier than the Aryans, with its oral tradition. Lastly, in its presentation of Shivaism, this work highlights the area beyond reality, which has always been man’s chief preoccupation: religion, in the primary meaning of the word. Shivaism seeks the ties between the different spheres of existence, investigates all the various paths, whether scientific, intellectual or artistic. Indeed, it is striking to note how close literary or artistic creation is to Shivaism, an “active participation in an experience that goes beyond and upsets the order of material life”. Thus, it is disturbing to read the Rig Veda description of Shiva’s companion “with his long hair, clothed with the wind”, or Daniélou’s explanation of Shivaite initiation as “the real transmission of a Shakti, or power, which takes the form of enlightenment”. We may think of Rimbaud, that wandering, lawless poet, author of enlightenment and “the man with the wind for his feet”.

Shiva and Dionysus “is not an essay on the history of religions”: the book opens with this disclaimer. It is much more, a multi-facetted text, like all the author’s works, an essay on the origins of human settlement, civilisations, social structures, languages and creation.

“This is an admirable book, copious, inspired, with prophetic insights on sacred dance, Tantrism, the Kali- Yuga. A book like this only appears once a year.”

Arnold Walstein, Astres, 1980.

CLIN D’OEIL

–  Archives-Souvenirs: two English translations of the Contes gangétiques (The Godsʼ Livestock).

Archives-Souvenirs: two English translations of the Contes gangétiques (The Godsʼ Livestock).

“The Game of Dice”, published by Barrie and Rockliff of London in 1965, and subsequently by Pan books in 1968 in “The Fourth Ghost Book” collection, edited by James Turner ;

The “Fools of God”, an English translation by David Rattray, published by Hanuman Books (Madras and New York, 1988).

This collection of tales, the original French version of which has seen several editions and reprints, is now ready for publishing in its entirety; English translation by Kenneth Hurry.

– ALICE BONER (1889-1981)

« Uday’s older brother, Ravi Shankar, had had a rather interesting career. The son of a highranking Bengali official, he had come to Paris to study painting. Pavlova, who was trying at the time to create an oriental ballet, took an interest in this boy who knew nothing about dance but had a great of imagination. He helped choreograph the ballet, which turned out to be very poor. It was here that he met Alice Boner, a Swiss woman from Zurich who had inherited a large fortune in industry. Alice took an interest in this very handsome Indian youth and decided to take him back to India so that he could devote himself entirely to dance. Alice was a beautiful woman of about thirty-five, tall and stately, haughty and strong-willed. She rather reminded me of Juno. She was also quite a good painter. She began to track down any surviving evidence of Indian classical dance, which was very much looked down on in Anglo-Indian cultural circles as were all the other traditional arts.

Alice was the first person to discover the great art of Kathakali dancing, which still existed in a few forgotten villages in the state of trichur in Kerala, in southeast India. She encouraged a local poet called Vallathol to bring together the best of the surviving masters of this remarkable art, and helped him found the Kerala Kala mandalam, the famous school of Kathakali, in the village of Chiruthuruthi. The school later became one of the greatest glories of India. It was she who discovered, helped, and supported the two splendid Bharata Natyam dancers, Bala Saraswati and Shanta Rao; she also knew many musicians, especially the famous Alla ud din Khân.

While living in Benares, Alice grew passionately interested in the aesthetics and symbolism of Hindu architecture and sculpture, which led her to the study of ancient texts. She collected a large number of manuscripts, but since she knew only a few words of Sanskrit, she enlisted the help of a few Indian scholars to translate them for her. She discovered unknown treatises of exceptional significance and, many years later, published some of these texts as well as her internationally famous studies on the architecture of temples, the best-known being her work on the construction techniques of the gigantic temple of Konarak. »

Alain Daniélou, The Way to the Labyrinth,, Memories of East and West, New Directions, New-York, 1987.

August 11, 1945, Almora (Himalaya)

Yesterday Alain Daniélou came to see me and I incidentally mentioned that I felt so desperately tired everytime I went up to Townshend in Kasar Devi Estate.

I said I did not know why this particular walk exhausted me so much, though it was not such a very long one. He quickly said : « It is the Devi ». I looked at him somewhat bewildered. So he went on and explained to me that at certain points of the earth there are particular stresses caused by superior powers, and that at such places temples are often erected. One ought not to live there, but only go there for worship. People here never go to that Estate without going to the temple and worshipping the Devi. Somehow he reasoning struck me and as I had not visited the Devi I thought it might be true. So at night in bed I concentreted on the Devi and tried to make contact with her. Everything became alive within myself and I started to realize the absurdity of my neglect.

I have been working for weeks now on my composition of Prakriti, but it never entered my mind to even pray to the Devi, to try to approach her, to identify myself with her, as I had done in the case of Vishnu’s Vishvarupa when, in a devotional spirit, I always tried to go beyond manifestation and to visualize the absolute. But the wonder of creation itself, the active manifesting power which had brought forth all these worlds, and was perhaps in the process of destroying them again, I always bypassed it, admiring it perhaps, but never workshipping it. There I found myself in an absolutely new position, face to face with the supreme creative power to whom we all owe our existence. I suddenly began to understand those who worship the Devi and was happy to have in some way seen the way leading to her. I decided to go to the temple with flowers and makes amends for my neglect. In the morning I plucked some roses from the garden and put them in a long boat-shaped vessel which I supposed represented the Devi’s symbol and prayed for her grace and mercy.

After that I worked merrily and felt quite relieved and happy and at noon a note came from Gertrude Sen, announcing the end of the war.

Alice Boner Diaries (India, 1934-1967) page 121

Luitgard Soni and Jayandra Soni, Eastern Book Corporation, New Delhi, 1993