EDITO

ALAIN DANIELOU ET LE MAHATMA

Alain Daniélou has often been unjustly blamed and criticised for his somewhat acerbic view of modern India’s greatest iconic figure, Mahatma Gandhi, whom he mentions to a greater or lesser extent in several of his works, viz. his autobiography, The Way to the Labyrinth, New Directions 1981; A Brief History of India, Inner Traditions International 2003; and in an article published in the French review Historia (Avril 1983) under the title “Le Prince et les Trois Larrons” (The Prince and the Three Thieves), which may be less widely known to English readers.

Alain Daniélou has often been unjustly blamed and criticised for his somewhat acerbic view of modern India’s greatest iconic figure, Mahatma Gandhi, whom he mentions to a greater or lesser extent in several of his works, viz. his autobiography, The Way to the Labyrinth, New Directions 1981; A Brief History of India, Inner Traditions International 2003; and in an article published in the French review Historia (Avril 1983) under the title “Le Prince et les Trois Larrons” (The Prince and the Three Thieves), which may be less widely known to English readers.

The recent publication of Pulitzer Prize winner Joseph Lelyveld’s “Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle with India”, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 2011, has received wide attention and caused a great stir on the Internet for its revelations of a Gandhi not entirely in keeping with the standard pious picture of the Father of Modern India. Furthermore, the picture painted by Lelyveld totally vindicates the negative view published by Daniélou decades earlier.

Daniélou’s views on Gandhi may be illustrated by an excerpt from his A Brief History of India, p. 311: “(…) shrewd and ascetic, ambitious and devout – one of those gurus who seem to exercise an incredible magnetism over the crowds and often lead them to disaster. (…)Practically, it was with him alone that the British Government ultimately decided the future of India, in which independence came about in the most disastrous way imaginable, leading to the partitioning of the country, one of the greatest massacres in history, the elimination of the social system and traditional culture, the suppression of the princely caste, the genocide of primitive tribes and the ruin of the artisan castes and their transformation into a miserable proletariat. All this was presented as progress.”

And from The Way to the Labyrinth, p. 179: “(…) Every day he had his legs massaged by young girls and insisted on sleeping beside one of them in order to test his chastity”. This report is borne out at length in Lelyveld op. cit., pages 303-307, “Perfection would be achieved if the old man and the young woman wore the fewest possible garments, preferably none, and neither one felt the slightest sexual stirring.

A perfect brahmachari, he (Gandhi) later wrote in a letter, should be ‘capable of lying naked with naked women, however beautiful they may be, without being in any manner whatsoever sexually aroused’”. Gandhi’s immense egotism beggars the imagination with his total lack of concern for the girl, viewed solely as his instrument. His behaviour was well-known among his entourage and gave rise to comment. “Nirmal Bose, (…) Gandhi’s Bengali interpreter, wasn’t initially judgmental (…) (b)ut his allegiance was gradually strained as he observed Gandhi’s manipulative way of managing the emotional ripples that ran through his entourage (…) ‘After a life of prolonged brahmacharya,’ Bose wrote in his diary, ‘he has become incapable of understanding the problems of love or sex as they exist in the common human place.’” (p. 307)

Although Gandhi belonged to the Bania (merchant) caste, he was sent to London to study for the Bar but, anxious to enter politics, he went on to South Africa. He was not yet the iconic figure in loincloth and homespun he later became on his return to India, but a properly-dressed, practicing lawyer who had espoused the cause of Indian indentured workers, inspired by the romantic socialist theories of Tolstoy and Ruskin. Lelyveld is enlightening with regard to Gandhi’s views on race. For Gandhi, equality meant that the Indian workers should be classed with the whites and not with the ‘Kaffirs’, who “are as a rule uncivilized (…). They are troublesome, very dirty and live almost like animals” (op. cit. p. 54). And again, “We believe in the purity of races as we think they (the whites) do” (op. cit. p. 58). Such comments speak for themselves.

What will come as a revelation to many is Gandhi’s very odd relationship in South Africa with the German Jewish architect Hermann Kallenbach, “the most intimate, also ambiguous, relationship of his lifetime (…) It was no secret then, or later, that Gandhi, leaving his wife behind, had gone to live with a man” (op. cit. p. 88). A much fuller description can be found on pages 88-97 of Lelyveld’s work.

It does appear, however, that at the end of his life, Gandhi felt some kind of self-doubt and, in “(s)peaking to an American professor in the first days of independence, he reflects that his career had been all along based on an ‘illusion’” (Lelyveld, op. cit. p. 327). Millions paid dearly for that ‘illusion’ in the massacres that preceded and followed Partition.

Even sadder is the reflection that the Partition itself and accompanying violence might even have been avoided without the baneful influence of Gandhi and his henchmen Jinnah and Nehru, both Western-educated.

Symptomatic was the resignation of Rabindranath Tagore and the withdrawal of other leading moderates from the Congress Party when Gandhi became its leader (A Brief History of India, pp. 313-315). The “Three Thieves” were largely responsible for hastening British withdrawal from India and supported the creation of East and West Pakistan according to Jinnah’s demands, with all the consequent horror and disaster.

This vindication of Alain Daniélou’s clear-sighted and truthful reporting on the Mahatma in the face of much ‘political’ opposition renews confidence in his views on much else in the contemporary world that run counter to prevailing wisdom.

Kenneth Hurry, Zagarolo September 2011.

– Parution en langue estonienne de L’Histoire de l’Inde

Editions Valgus, Talinn, 2011.

ISBN: 978-9985-68-265-4

Alain Daniélou approaches the history of India from a new perspective–as a sympathetic outsider, yet one who understands the deepest workings of the culture. Because the history of India covers such a long span of time, rather than try to create an exhaustive chronology of dates and events, Daniélou instead focuses on enduring institutions that remain constant despite the ephemeral historical events that occur. His selections, synthesis, and narration create a thoroughly engaging and readable journey through time, with a level of detail and comprehensiveness that is truly a marvel.

Alain Daniélou approaches the history of India from a new perspective–as a sympathetic outsider, yet one who understands the deepest workings of the culture. Because the history of India covers such a long span of time, rather than try to create an exhaustive chronology of dates and events, Daniélou instead focuses on enduring institutions that remain constant despite the ephemeral historical events that occur. His selections, synthesis, and narration create a thoroughly engaging and readable journey through time, with a level of detail and comprehensiveness that is truly a marvel.

A Brief History of India

Inner Traditions International, Rochester, 2003 / The first English translation of the second edition of the work awarded the French Academy Prize in 1972. Translation by Kenneth F. Hurry.

Valgus Publishers is one of the oldest publishing houses in Estonia. Our most significant dictionaries and reference books include German-‐Estonian Dictionary (ca 65 000 entries), Latin – Estonian Dictionary (more than 30 000 entries), Lexicon of Foreign Words (more than 32 000 entries), Estonian-‐ German Dictionary (ca 70 000 entries) and Swedish-‐Estonian Dictionary (ca 100 000 entries). Estonian-‐Swedish Dictionary (ca 80 000 entries) and Estonian-‐French Dictionary (ca 50 000 entries) will be available by the end of 2012.

In the end of 2009 ABC of Family Health was published, produced with the cooperation of more than hundred Estonian doctors and scientists.

History is one of our priorities. Our short history series includes such titles as A Short History of Germany by Hager Schulze, A History of the United States of America by Philip Jenkins, A History of the British Isles by Jeremy Black, A History of France by G. Labrun and P. Toutain and A History of Spain (ed. R. Carr), A History of Ireland by Mike Cronin and A History of China by J.A.G. Roberts. Short histories of Japan, India will follow in 2011. A Concise History Of Russia (Remote, Yet Close) is one of our bestsellers, written by reknowned authors David Vseviov (Ph.D.) and Vladimir Sergejev (Ph.D.).

For a full list of our publications and further information please visit our website at

ÉVÈNEMENTS

– 50 anni a colle labirinto:

On Sunday, September 18 2011, the Harsharan Foundation, set up by Alain Daniélou in memory of his friend the Swiss photographer Raymond Burnier, celebrated its fiftieth anniversary at Zagarolo, near Rome. The evening started with a reception hosted by Harsharanʼs director, M. Jacques Cloarec, at the Alain Daniélou Study Centre. Guests included numerous friends from the village, from Rome and from many other parts of the world.

The celebrations then moved on to a renovated Palazzo Rospigliosi where they were welcomed by the authorities: the Mayor of Zagarolo, Dr Paniccia; the director of the Institution Palazzo Rospigliosi, Dr Mariani; Dr Agnihotri, the First Secretary of the Indian Embassy in Rome, who had given their patronage for the evening, and M. Cloarec.

The guests – now boosted by many from the vicinity – admired an exhibition of fine photographs, from those taken in India by Daniélou and Burnier to more recent ones by M. Cloarec and Giorgio Pace, as well as Italian translations of several of Daniélouʼs books and the CD sets of Indian music issued by the Foundation.

After refreshments, about 180 guests enthusiastically applauded the artists in a highly professional exhibition of Indian dance and music. The show included a vina solo of Carnatic music by Raghunath Manet, the groupʼs well-known leader, a tabla solo by Ahmed Khan Larif, and Bharata Natyam dances by Raghunath Manet, Thérèse Mercy, Nivita Bergen.

Our thanks to M. Cloarec and to the organizers for a delightful evening.

Kenneth Hurry.

Photos : Mario D’Angelo

Photos : Mario D’Angelo Photo : Mario D’Angelo

Photo : Mario D’AngeloALBUMS

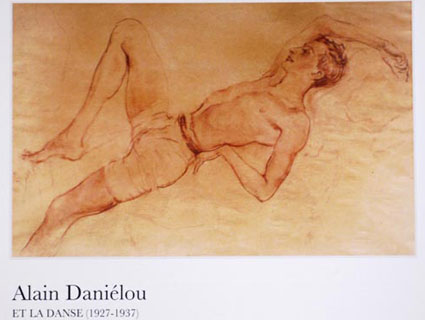

–Alain Daniélou and Dance (1927-‐1937)

With a view to preserving these old photos and revealing a little-‐known side of Alain Daniélou – his career as a dancer in the ’thirties -‐, the Alain Daniélou Study Centre has produced this album, which brings to life part of his artistic life prior to his departure for India, where he would dance for the poet Rabindranath Tagore.

Once settled in Benares in 1937, he abandoned dance to study Indian music, learning to play the Vina, before devoting himself to Hindu tradition, culture and philosophy.

In 1994, his friend, the composer Sylvano Bussotti took an interest in the music composed by Alain Daniélou in his youth, and published a small collection “Quatre danses d’Alain”, which he completed. These dances have been performed by the artist Toni Candeloro, and by others.

Alain Daniélou Study Centre, April 2011