EDITO

Dear and Faithful Readers of the Harsharan Foundation Newsletter.

Dear and Faithful Readers of the Harsharan Foundation Newsletter.

Our Foundation is undergoing a total transformation, and I am for the last time writing this editorial in the name of the Harsharan Foundation.

The photographer Raymond Burnier, who was at Alain Daniélou’s side during the two decades he remained in India and was his companion for 38 years, died dramatically in 1968. Alain Daniélou immediately (1969) set up the Harsharan Foundation; Harsharan was Burnier’s Indian name and they had both been accepted into the Hindu world.

Daniélou made over to the Foundation the capital he inherited, plus the property he had purchased near the village of Zagarolo close to Rome. This estate then became, particularly during the ’eighties, when Daniélou settled there permanently, a venue for meetings with and the reception of very different figures, from the choreographer Maurice Béjart to the King of Afghanistan, from Mahler’s biographer Henry-Louis de La Grange to the painter Mac Avoy.

It was only after Daniélou’s own death in 1994 that I came to realise that he had strictly followed the four Hindu rules of life and, in particular, the last, “Moksha”, liberation, by disposing of absolutely all his assets before the end.

He left so many ‘works in progress’ that for the next decade the Foundation had no difficulty in continuing its activities. Then, little by little, without its helmsman, it started to lose vitality.

Since 2007, the auspicious year marking the centenary of Daniélou’s birth, I started on a quest to seek organisations with which we could collaborate.

At the end of 2011 I had the great joy of convincing my friend Ion de la Riva Careaga Guzman de Frutos, the brilliant Spanish diplomat and creator of Casa America in Madrid, of the Spanish Cultural Centre at Havana and Casa Asia at Barcelona, which has become a centre of prestige, recently Spain’s ambassador to India and then to UNESCO, to take over as Director of our Foundation.

There is no doubt that his energy, his ability and his enthusiasm will perform miracles in restoring the vitality of our organisation, all the more so because he is an excellent friend of India and has been greatly influenced by the work of Daniélou.

Our statutes have been changed to extend our field of action, and the Foundation’s name has been changed to: Alain Daniélou Foundation.

In the very next letter to be addressed to you under this new name, our Director General Ion de La Riva will outline his projects and the guidelines he wishes the Foundation to follow.

It goes without saying that 2012 has been an extremely full year, with many changes still in progress.

The Zagarolo Centre will retain its name as the “Alain Daniélou Study Centre” and major transformations will enable it to receive a greater number of visitors and residents. The Rabindranath Tagore Auditorium has been created, a very welcoming area with excellent acoustics, which can seat up to 150 persons, to be used for entertainment, concerts, seminars, workshops, and conferences.

A media library is currently being set up. The auditorium was gloriously inaugurated by the visit of 15 musicians of the Paris Orchestra, who enlivened the house for a week: an ultra- professional team, but also cheerful young people who rounded off their stay with a public concert.

Among the year’s other activities, we are installing an Internet on-line database, as well as bringing out e-book editions of all Daniélou’s works by setting up a suitable publishing house. Re- editions in this format will soon be on line.

Two projects concern the Semantic, the micro-tonal musical instrument built according to Daniélou’s theories: the more concrete project has been practically achieved; the ‘virtual’ project, on the other hand, will provide direct Internet access both to Daniélou’s theory and to the instrument itself.

As usual, the year was brought to a close traditionally at the Daniélou Centre’s Labyrinth by the festival of the Winter Solstice on 21 December, with a concert of Indian music for the occasion and the transfer of powers from me to Ion de La Riva.

All my best wishes to Ion de La Riva for the accomplishment of his new activities. All my New Year’s wishes to you, dear Readers, who have been with us for so many years.

Jacques Cloarec, Lausanne, 29 December 2012

Translated into English by Kenneth Hurry.

NEWS

2013 will see the publication of the critical edition of Rabindranath Tagore’s eighteen Songs of Love and Destiny, translated into English and French and transcribed for piano and voice by Professor Daniélou. As editor of the project, I should like to share with the readers of Alain Daniélou Actualités the spirit and substance that crown a complex and many-facetted work started in 2007.

The eighteen Songs are Daniélou’s response to the Poet’s request that Western audiences should not only share the lyrics, but also their accompanying melodies, in a musical context more familiar to them. Up to now, very few readers and fans of Tagore have been aware of his impressive musical production. In India, his melodies are a well-known heritage, taught in schools and performed both at home and in concert halls, far beyond the borders of Bengal. Even the national anthems of India and Bangladesh, both text and music, are his creation.

The universal nature of the message of Tagore, Nobel Prize for literature in 1913, is clear from a very first reading. His poems are directed to all, intimately and collectively, while the music reflects the influence of classical and semi-classical styles in vogue at the time of his artistic training: the khyal, the dhrupad, the devotional music of the Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, and of the mystical Bauls, the wandering poet-musicians of Bengal.

The vocabulary, the ways in which it is transmitted and performed, the very sonority of Indian music, differ greatly from its western counterpart. First as a musician and then as a musicologist, Daniélou was familiar with both languages and, at that time, was the only person alive capable of carrying out Tagore’s request and provide the world with its first specimen of musical fusion. In France, the 19th century had been marked by a certain exoticism, whether naturalistic (Bizet) or manneristic (Félicien David, Meyerbeer, Massenet, Delibes, Saint-Saëns) and thereafter the Parisian avant-garde was not lacking in noteworthy examples of arrangements of melodies from distant parts, inserted in a complex, modern harmonic and instrumental framework (Debussy, Stravinsky, Ravel). Although the attitude toward “exotic” material during the Romantic era had the same traits as a pretty drawing-room water-colour and, during the 20th century, of conscious borrowing, Daniélou’s position was wholly new and different, even from the rigorous conceptions of musicians and ethno-

musicologists such as Bartòk, Kodaly and Brăiloiu. Indeed, the mandate Daniélou had to carry out was a very precise one, and he tackled it with the respect and humility of an amanuensis; at the same time, his humility does not make his contribution flat and dull and he manifests his considerable experience as a musician familiar with the repertory and styles of his period, making simultaneous choices of feeling and reason. Amongst these many choices, the first and most evident is his choosing the piano as an accompaniment, and the second is the consequent reference to genres such as the romantic German lied and the French chanson, symbolist and impressionist. At the same time, Daniélou never hid his preference for Schubert, Fauré, Duparc. Such forms, seemingly essential considering Daniélou’s historical context, operate perfectly when it comes to Tagore: Lied and chanson are chamber music or, better still, for the home in the sense of Hausmusik, a concept very close to Tagore’s own in India, where the Rabindra Sangeet (literally: Music by Rabindranath, understood as a lyrical-musical corpus) was and is frequently accompanied by a simple harmonium in the context of the home, rather than the concert hall.

A sentimental and reasoned approach, suggested by Daniélou’s own example, experimented and consolidated over the past five years, constitutes the peculiarity of an editorial project aimed at spreading and facilitating a musical work that has long been avoided and misunderstood by western performers. Attempts at having it performed by famous musicians left both performers and Daniélou himself dissatisfied. Nowadays, western musical circles are more receptive and better prepared than they were a few decades ago and the assimilation of non-European cultures by the West means that today’s musicians approach it with fewer problems.

The plunge I am about to take is, however, more ambitious: not only that of placing the eighteen Songs in the context of 20th century repertory, as an original and successful attempt at bringing eastern melodies and texts closer to the West, but also that of fostering their “return home”. Spurred on by the success of the numerous performances staged by Francesca Cassio and myself in India and Bangladesh, I shall edit an edition for Indian and Bangladeshi performers who wish to use the piano accompaniment instead of the traditional arrangements, also utilising both the Roman and Bangladeshi alphabets. Furthermore, the number of Indian musicians turning to European music and the piano is constantly growing, just like the number of western musicians studying Indian music. A cutting-edge edition cannot ignore the impact of globalisation, which makes it easier to share models and resources once confined to local cultures. Daniélou looked askance at any mixture of cultures, castes and races, as he did at any kind of religious syncretism. Understanding the meaning of his statements is the task of a dedicated analysis, in view of the unseemly exploitation and criticism that he inevitably attracted in expressing his ideas. The universal nature of Tagore’s message, however, his vision of life, the world and existence, range far beyond any national or cultural frontiers, so that the uniting of these musical languages has, in this case, the same semantic and sociological value as a literary translation, an art at which Daniélou excelled.

This editorial project substantially surpasses the De Maule edition of 2005, with its evident limitations owing to the reading format, typographical errors and the absence of any critical- musicological apparatus needed for an exhaustive and modern publication used by musicians.

The new edition will avail itself of an easy electronic format and the text will be provided in English, French and Bengali, in both Bengali and Latin alphabets, with accurate transliterations in IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet). A short account will be given of the rāgas (modal and psychological contexts) from which the melodies originate, as indicated in Daniélou’s own manuscripts. The transliteration of the Bengali text used in Daniélou’s manuscripts will be replaced by a transcription that is more intuitive for the western performer and more in line with modern international standards. It should be noted that, in his notes dated 1991, for some of the song titles Daniélou had already abandoned the transcription criteria previously adopted. Numbered end notes will indicate any significant discrepancies between the sources (the several manuscript versions, drafts, previous editions) and unpublished alternative musical arrangements will also be included.

To support me in my work, I have called upon two specialists who are deeply in contact with Indian and Bengali culture, Dr. Francesca Cassio and Prof. Mario Prayer. Francesca Cassio, currently associate professor and chair in Sikh Musicology at New York’s Hofstra University is the first artist to perform the whole eighteen songs according to Daniélou’s version, both live and on compact disc. Dr. Cassio studied the Rabindra Sangeet at Kolkata and Shantiniketan, where she was Visiting Professor in Musicology at Visva Bharati University, founded by Tagore himself, thus drawing on the original

source and deepening the repertory with specialised artists. She will present a paper on the vocal performance of these songs in the context of Daniélou’s work. Mario Prayer, lecturer in Bengali language and translation at Rome’s “La Sapienza” University, will contribute a section on the poetics of the eighteen Songs, with an appendix on the phonetics of the Bengali language. To him and to Giulia Gatti we owe the most wonderful translations of some of Tagore’s lyrics, which have inspired Francesca Cassio and me in our musical interpretations.

Rome, October 2012

Ugo Bonessi.

Translated into English by Kenneth Hurry.

[Ugo Bonessi, pianist and musicologist, together with Francesca Cassio made the first recording and complete performance of the eighteen Songs in concert form (Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata, Dhaka) utilising them for the realisation of the work “Opera of Love and Destiny” (Opera d’Amore e Destino) in 2007 (Rome, Zagarolo, Bergamo) and in the play “Dell’Amore e del Destino” in 2011 (Rome). The recordings were made using Alain Daniélou’s one-hundred-year-old piano, in the library at the Labirinto, the villa in the Roman countryside in which he lived from 1961 onward and which today is the Italian seat of Alain Daniélou Foundation. The CDs are published and produced by the Harsharan Foundation – Alain Daniélou Study Centre with the collaboration of Visva Bharati University and with the label of Questz World of Kolkata, India]

HISTORY / MEMORIES

Ravi Shankar jouant de l’esraj, (Calcutta, 1934). Photo Alain Daniélou.

Having covered the entire length and breadth of our great heritage during his long span, so deep were his feelings for the Motherland that he embraced Hinduism and took the name of Shiv Sharan. Thus began the incessant flow of his glorious writings on Indian culture especially covering music, philosophy and religion. To this day his continuous contribution to the promotion of India’s culture heritage abroad through his works has no parallel in modern history. His unflinching devotion to our culture and, above all, love for Mother India, defy all expression. It would not be an exaggeration to call him the modern Max Müller .

Such “sons” of our country, in spite of their alien birth, belong to this country with all their heart and soul.

Ravi Shankar

Musician

Member of Parliament

(Rajya Sabha)

Lettre à Narasimha Rao

Minister of Human Resources Development New Delhi le 18 Septembre 1987.

YOUTUBE

Tagore’s Songs of Love and Destiny

Translated and specially transcribed for voice and piano by Alain Danielou (1907/1994) Presented by Francesca Cassio (vocalist) and Maestro Ugo Bonessi (piano)

Introduction and presentation of Tagore’s songs in Bengali by Dr. Reba Som Collaboration: Italian Embassy Cultural Institute; Alain Danielou Center; and Delhi Music Society,

Rabindranath Tagore Centre, ICCR, Kolkata

WORKS

AMELIA CUNI

At this LINK, you can download a PDF with my latest essay on the interpretation of the John Cage RAGAS (SOLO 58, Song Books, 1970) published in the Journal of the Indian Musicological Society, Vol. 41, Mumbai, 2011-2012

http://www.ameliacuni.de/amelia/Cuni_JIMS.pdf

ARCHIVES

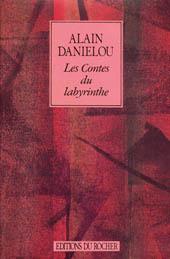

This title comprises five tales, placed in the Lazio region, south of Rome. The tutelary image of Daniélou’s work, the labyrinth is also the name of the area he chose as his home on returning to Europe.

This title comprises five tales, placed in the Lazio region, south of Rome. The tutelary image of Daniélou’s work, the labyrinth is also the name of the area he chose as his home on returning to Europe.

These short stories are largely autobiographical, particularly the tale of Tages and the two friends Gwyn and Arno, harking back to Alain Daniélou’s early days in the Roman countryside, its discreet paganism and closeness to nature not unlike India, his country of choice for thirty years. “The Sun’s Gift” [Le don du soleil] makes this connexion explicit. Daniélou’s protagonist is a young Roman, Ludovico, who, fascinated by the atmosphere of the Sun Temple during a trip to India, learns that Shivaism, the cult practiced there, had its match in the West in Mithraism. Catholicism, although initially very close to Mithraism, came to oppose its values and banned the Mithraic cult. While Catholicism ostentatiously triumphs throughout this area, the fiefdom of the pope, paganism animates nature, the nymphaea and mithraeums lost beneath the foundations of its churches. It is consequently not astonishing when events occur that are incomprehensible for westerners saturated with rationalism or Catholicism, like the collapse of a dam, persons disappearing only to reappear in a wholly different context, having forgotten their earlier adventure. Having lost immemorial knowledge, convinced that modernity holds the key to happiness and desirous of imposing it on the entire world, people are surprised when these despised archaic societies win the contest against their imperialistic and ill-omened projects by mysterious means beyond their understanding. In his light and didactic style, Alain Daniélou once more tackles the key themes of his work: warning against a levelling and destructive colonialism, and recommending the harmonious knowledge of ancient civilisations, in which ethics and aesthetics are never separate. In this book, Alain Daniélou discovers for us an enchanted world in which the supernatural is an everyday event.

Anne Prunet, Marie-Laure Bruker.