EDITO

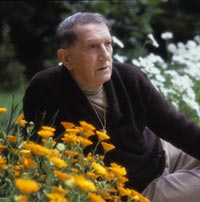

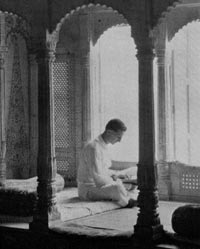

Alain Daniélou, Zagarolo, Rome,1985, Photo J E. Cloarec.

Published in 11 languages – French, English, Italian, Spanish, German, Dutch, Romanian, Bulgarian, Portuguese, Tamil and Japanese – Alain Daniélou’s work is currently available in 15 countries. His multi-faceted work appears to attract the interest of an increasing number of readers. One of the reasons for such interest is certainly his Hindu-Shaivite view of the world, to which he bore witness and whose frontiersman he became, dealing with subjects that have become immensely urgent for mankind’s survival on this Earth. At the same time, for centuries India has acted as a laboratory in the cohabitation of peoples of different languages, cultures, origins and religions – a fact that is of great interest to our shattering western society – and is a source of information at the present time of globalisation and major population migrations.

During this year – 2007 – and extending into 2008, we shall be commemorating the centenary of the birth of this author, who defies all classification and who lived through the past century in such a fantastic fashion. This 13th newsletter provides information about the various events and publications being prepared in France, Belgium, Italy, Spain, Germany and India.

In particular, I wish to highlight the culmination of a project in the musical field, started by Alain Daniélou in 1936 with Maurice Martenot. Indeed, the microtonal instrument known as the Semantic Danielou is of interest to several composers, and compositions are currently being prepared for it. The first has already been completed: it is called “Ahata-Anahata”, a work by Igor Wakhévitch, extracts of which can be found on our site, which has been totally restructured.

The second composition now in progress is a work by Jacques Dudon, who will present it at a concert to be held this autumn. The instrument will then go to Naples, where the composer Luigi Esposito is preparing a third work. A new edition of the book “Sémantique Musicale” – the third since 1967, with a new preface by Jacques Dudon – will also be published very soon by Editions Hermann.

At the defence of the thesis of Madame Anne Prunet at the University of Paris VIII with the title “Victor Segalen, Michel Leiris, Alain Daniélou, Nicolas Bouvier, poétiques du voyage”, I was surprised by the agreement of all the members of the jury that the most successful and most interesting part of the thesis was the one concerning Alain Daniélou.

Since they will be taking place before our Summer Solstice newsletter, we must advise our readers of the Dhrupad concert at the Bodemuseum in Berlin by the Gundecha Brothers and Amelia Cuni on June 9 and the presentation at Rome’s “La Sapienza” University on April 2 of the book “Il Tamburo di Shiva”, the translation of “The Music of Northern India”, published by Casadeilibri of Padua. A Bharata Natyam show is also scheduled at Padua by Anusha Subramaniam (1) for June 30.

Happy Spring Equinox!

JC.

(1)- Anusha Subramaniam

Anusha Subramaniam is one of the best known faces of Bharatanatyam dance in the UK. An alumni of Kalakshetra, she is part of the long tradition that has revitalised, restructured and re-interpreted Bharatanatyam in a contemporary context. As a solo dancer Anusha has performed at many prestigious venues for a variety of appreciative audiences internationally. She regularly collaborates with other classical and contemporary performing artists exploring and expanding the vocabulary of dance and music. Most recently she collaborated with Dance Alloy (USA) and Arangham (India). Director of Beeja, she is also a teacher, choreographer and dance movement therapist.

ACTUALITÉS

– The Alain Daniélou Centenary Year (1907-2007)

Projects

April 2007: – Presentation the 2 april: “Il Tamburo di Shiva” at Rome University La sapienza: publishers Casadeilibri, Padova. With presentation by Lorenzo Casadei, Jacques Cloarec et Giorgio Milanetti.

June 2007: – Reprinting of “Sémantique Musicale”, Editions Hermann, Paris.

– At the Bodemuseum in Berlin, 9 June: Dhrupad concert with the Gundecha Brothers, Amelia Cuni and eventually an instrumentalist (and Peter Pannke to give some personal readings)

– Concert of Bharatanatyam in Padova (Anusha Subramaniam + 3 musicians), homage to Danielou, the 30 June 2007, during the Portello River Festival.

– Publication of “The Way to the Labyrinth” in Spanish; publishers Kairos, Barcelona.

September 2007: – Publication of “Images from the musical life in India 1935-1955 ”; Editions Michel de Maule, Paris.

– Saturday, 22 September: Concert at the Thoronet with the Jacques Dudon ensemble, including the Semantic Danielou, Santour and Sitar.

– Saturday evening, 29 September: same concert at the Palazzo Rospigliosi at Zagarolo, and eventually in Rome on Sunday 30.

October 2007: – Publication of the “Tour du monde en 1936” with drawings and photos: Editions du Rocher.

– The 6 or 7 october 2007, Concert at Paris or Vitry-sur-Seine with the Jacques Dudon ensemble, includind the Semantic Danielou, Santour and Sitar.

– The exhibition “Lumières de l’Inde” will be on show at Hainaut as part of the event “La Fureur de lire” throughout Belgium.

– With the occasion of the India-Spain node, presentation of the Spanish edition of “The Way to the Labyrinth the 16 october 2007 and exhibition of the photographs drawn from the work: “Images from the musical life in India 1935-1955 ”. from 16th of October until 16th of November both at the Casa de India at Valladolid

– Concert of the students of the Center of the Cini Foundation in Venice the 25 October 2007.

– New corrected edition of the “Chemin du Labyrinthe”, preface by Jacques Cloarec and new photo selection, Editions du Rocher. Paris

November 2007: – Seminar in India on the theme: “Europeans in India in the light of the rediscovery of Indian culture in the twentieth century”.

– Exhibition, Concert of songs by Rabindranath Tagore, arranged by Alain Daniélou, concert with the Semantic Daniélou at Berlin in november at the Dahlem Museum.

– Exhibition and concert of Francesca Cassio (Dhrupad) at the Vicenza Music Academy.

– Planned publications:

« Hindu Polytheism »,in spanish, Ediciones Atalanta, Girona, Spain.

« Shiva and Dionysus » in japanese, Publishers Kodansha, Tokyo.

« The Way to the Labyrinth – Memories from East and West » and « Virtue, Success, Pleasure and Liberation, Traditional India’s social structures, The four Aims of the Life in the Tradition of Ancient India », in Hindi, Publishers Yatra Books, New Dehli, India.

« A Brief History of India» and « Hindu Polytheism », in portuguese, Publishers Madras Editora, Sâo Paulo, Brasil.

« Manimekhalai, The Dancer with the Magic Bowl », Publishers Kaïlash, Paris Pondichéry.

– Les Cahiers du Mleccha – Vol IV.

Réimpression en cours dans la collection : Les Cahiers du Mleccha, du volume :

Réimpression en cours dans la collection : Les Cahiers du Mleccha, du volume :

Approche de l’hindouisme, éditions Kaïlash, Paris-Pondichéry.

This Approach to Hinduism, appearing ten years after the death of Alain Daniélou, provides important data on the tolerance and incredible richness of traditional Hinduism, in which “since the beginning, scholars and philosophers have studied, without prejudice, the enigma of man and the universe, have sought to understand, to know, not to believe or preach”. In the Hinduism that Daniélou got to know through its arts and sciences, through Yoga, its concepts of death, love, social life, or even drugs, the co-existence of opposites is always “where the divine lies”.

Thus, any westerner travelling to India is rarely insensitive to that simple but relaxed, reverent but courteous relationship of the Hindus with the gods, with flowers, scents, the ornamental animals in the temples, music, the beauty of rites, statues and ceremonies. What is striking is that it appears not to be a question of “belief” – with all that the word implies of voluntary sentimentality and deadening of the critical spirit -, but a spontaneous, cosmic sympathy, the happy bathing in a natural harmony that we ourselves have lost.

– INDIA – EUROPE, EXPERIENCE OF THE ARTS

Alain Daniélou, Stella Kramisch, Alice Boner, and the rediscovery of Indian culture in the 20th century.

Proposed by The India-Europe Arts and Philosophy Committee

Samuel Berthet, Dagmar Bernstorff, Renuka George, Lakshmi Subramaniam

I. THE PROJECT

Since the Antiquity, India – its wealth, its culture – became a source of imagination for Europeans travellers, philosophers, artists and rulers (The way of Life of the Brahmans, by Saint Ambrose, Indica by Arrian, etc). Accurate Representations of India or phantasmagorical ones through oral and written accounts given by travellers were a source of inspiration for European s during the Middle Ages, as land and sea travellers commuted between the two part s of the world through the spice route and the silk route, i.e. via Arabia and the Persian Gulf The writings of Marco Polo, Dante, Ibn Batuta, Wolfram von Eschenbach and the Indian collection of fables, the Pancha Tantra are the most famous works among the various references made to India. The discovery of the Atlantic route opened a new era of contacts, exchanges and therefore representation.

Soon, Europeans commissioned Indian artists to paint the subcontinent’s people and their life (Portuguese collection, Manucci, Le Gentil), or took up the challenge themselves (Van Linschotten). Along with those different contacts started a period of exchanges and rivalries, but also a period of syncretism, discoveries, technological transfer, studies, and innovations.

Those cultural exchanges, in which Indian knowledge was often a source of inspiration, became very important for world cultural, scientific and economic evolution.

At the end of the eighteenth century, the studies of William Jones and Anquetil Duperron gave momentum for the creation of a science devoted to the study of Indian culture through a study of Indian manuscripts with a humanistic perspective: the discipline of Indology. But the following century witnessed an ideological change with Europe asserting its domination over many regions of the world leading to what later will be called Orientalism.

The century of Macaulay tended to draw the values of Indian culture into the shadow, while the colonial ideology extended its grasp over westerner’s minds, promoting a Europecentrist vision of the world. Material development tended to eclipse cultural values. The Indologists in the German speaking academe, on the other hand, who had no experience of colonialism, practiced their studies of Sanskrit and ancient manuscripts in the ivory towers of universities, without ever travelling to India.

In this context, the works of European scholars, starting from the 1920’s and 1930’s, such as the Austrian art historian Stella Kramrisch, the Swiss sculptress Alice Boner, the French musicologist, linguist and scholar of religions Alain Daniélou and the German student of Sanskrit Alfred Würfel, who went to India to study and experience Indian culture directly and on their own initiative, unfettered by institutionalized research -contributed to a real rediscovery of Indian culture in collaboration with Indian intellectuals and artists. Though these works correspond to those personalities’ own itineraries, they interacted, given their exceptional sensibility for the arts, often guided in their exploration by Indian artists (Rabindranath Tagore, Uday Shankar, Omkarnath Thakur) and artisans. Their work is first of all based on the reading of original manuscripts in Indian languages (Sanskrit, Pali, Hindi, Tamil, etc), but also on the analysis of architectural, musical and visual concepts, combined with those scholars’ own experience of Indian arts.

In this context, the works of European scholars, starting from the 1920’s and 1930’s, such as the Austrian art historian Stella Kramrisch, the Swiss sculptress Alice Boner, the French musicologist, linguist and scholar of religions Alain Daniélou and the German student of Sanskrit Alfred Würfel, who went to India to study and experience Indian culture directly and on their own initiative, unfettered by institutionalized research -contributed to a real rediscovery of Indian culture in collaboration with Indian intellectuals and artists. Though these works correspond to those personalities’ own itineraries, they interacted, given their exceptional sensibility for the arts, often guided in their exploration by Indian artists (Rabindranath Tagore, Uday Shankar, Omkarnath Thakur) and artisans. Their work is first of all based on the reading of original manuscripts in Indian languages (Sanskrit, Pali, Hindi, Tamil, etc), but also on the analysis of architectural, musical and visual concepts, combined with those scholars’ own experience of Indian arts.

The studies of Kramrisch, Boner and Daniélou on Indian art have influenced deeply the renewal of western contemporary art, and Danié lou’s works devoted to Indian music in a comparative context have been instrumental in forging the concept of world music. The works of those European scholars have led to the creation of sometime extensive collections of Indian manuscripts, of photo archives (like Alain Daniélou and Raymond Burnier’s collection), as well as drawings, a valuable material for the study of Indian history. Their itinerary along with those of their Indian counterparts (Uday Shankar, Rabindranath Tagore, Dagar brothers, etc.) draws a map of a network of cultural life, the major sites being Calcutta, Santiniketan, Varanasi, Almora, Adyar on the one hand, Paris, Lausanne, Zurich, Berlin and Rome on the other. Deprived of the colonial bias both the studies and the material collected deserve a scholarly and illustrated rediscovery.

Scholars and artists have decided to come together under the India-Europe Arts and Philosophy Committee to propose a multimedia approach to the cultural heritage born out from long exchanges between India and Europe. It has chosen for its first event to focus on a particularly important character, namely Alain Danielou.

Born on the 4th October 1907, the life and the work of Alain Daniélou have paved the way to assessing the value of non European art, and especially music, in the western world and within world institutions. His life and work in India have been central in his scholarly and philosophical formation. He collected thousands of manuscripts on Indian music, and initiated the first collection of non European music of world standard.

Born on the 4th October 1907, the life and the work of Alain Daniélou have paved the way to assessing the value of non European art, and especially music, in the western world and within world institutions. His life and work in India have been central in his scholarly and philosophical formation. He collected thousands of manuscripts on Indian music, and initiated the first collection of non European music of world standard.

His very personal relation to India, marked by collaboration with some of the greatest artists of his time, such as Rabindranath Tagore or Omkarnath Tagore deserves therefore a complete survey, as well as an academic reassessment. Except manuscripts and recordings, Daniélou and Burnier have also left valuable photographic archives as well as drawings and paintings, along with correspondence.

II. PROGRAMMES

In India: India International Centre and Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (New Delhi).

1. WORKSHOP ON DANIELOU AND HIS CONTEMPORARIES:

Date: 4 October 2007, the 100th birthday of Danielou in Benares

Participants: 10-12 scholars from India and abroad

To take stock of the ideas and the collection of sources of Daniélou , Alice Boner and Stella Kramrisch

Venue: preferably Alice Boner House at Benares

CONCERT

Berlin June 9

Dhrupad Concert by the Gundecha Brothers and Amelia Cuni at the Bodemuseum

Concerning the Dhrupad

When Alain Daniélou returned from India to Europe in 1958 he was stupefied at Western ignorance of the music of Asian countries. In record shops, a Sicilian lullaby and Breton bagpipes stood side-by-side under the heading “Folklore” with the Imperial Japanese Court Orchestra and performers of Indian, Chinese or Iranian art music. Nothing seemed to have changed since Berlioz wrote:

“I must end by saying that the Chinese and the Indians would have music like ours if they had any at all. In this regard, however, they are still plunged in the deepest darkness of barbarity and in a childish ignorance, just revealing a few vague and feeble instincts. Moreover, the Orientals call music what we would call a racket, so that for them, as for the witches in Macbeth, what is horrible is beautiful.”

Alain Daniélou also rebelled against ethno-musicological research methods and the institutions promoting them. He felt that studying the music of the East on the basis of Western conceptions and using the Western system was a total aberration. A pianist and lieder-singer himself – as well as a player of the Indian Vina, he was well-placed to change people’s minds, which he managed to achieve by modifying ethno-musicological approaches.

With his usual enthusiasm, he launched out on a task of reassessing, promoting, spreading, conserving and developing the art music of the Orient, and particularly the great Japanese, Chinese, Indonesian, Indian and Arabic-Persian traditions.

He immediately found enthusiastic support in the just-created UNESCO, which, at the beginning of the ’sixties, asked him to produce a major record collection of such music – the “Musical Anthology of the Orient2” –, published starting from 1962 by Bärenreiter/Musicaphon of Kassel and now available on CD, published by UNESCO.

Essential support was also forthcoming from one of the past century’s major figures in international music, the Russian composer Nicolas Nabokov, a great friend of Stravinsky, Balanchine and others, and adviser of the Berlin Senate on cultural affairs, as well as director of the Berliner Festwochen.

Nabokov, who had been a friend of Daniélou’s since his wild years in Paris and had visited him during his stay in India, obtained a major grant from the U.S. Ford Foundation for the purpose of setting up in West Berlin – in the middle of the Cold War – the Internationales Institut fûr vergleichende Musik Wissenschaft and Documentation, of which Daniélou became the founder and first director in 1963.

The political aim was clear: the West desired to create a dynamic city of cultural and artistic attractions in West Berlin, an enclave in the midst of the new USSR empire.

Daniélou took advantage of the situation and his work, as indicated above, was immense. One of his first activities in Berlin was to continue the UNESCO record collections and bring to Europe groups of classical musicians from the East, the first of whom were the Dhrupad singers Mohinuddin and Aminuddin Dagar, who did a major European tour and took part in the 1964 Berlin Music Festival at the Palace of Charlottenburg.

Daniélou met with difficulties from the Indian authorities who did not wish to allow this group of singers to come, since they represented a particularly difficult and austere tradition that had been almost totally abandoned in India. Their tour was an immense success, not only allowing western audiences to discover a wholly unknown form of classical music at the highest level of quality, but also arousing new interest within India itself for this kind of singing. Nowadays, many groups of Dhrupad singers have taken up the torch: each year a festival of this unique kind of singing is held at Varanasi, and it is also performed by western singers such as Amelia Cuni in Berlin and Francesca Cassio in Italy, who also give concerts of this subtle music form.

Daniélou’s task did not come to a halt when he left the Berlin Institute in 1979. Thanks to the many groups invited, to the concerts and mini-festivals organised in Berlin, the Institute aroused much interest and produced specialists in this field who were among the first in the West to reassess this traditional art music.

Daniélou’s work is unanimously recognised and won him numerous awards in many countries, as well as the support of figures of great prestige, such as Yehudi Menuhin, a member of the Institute’s scientific council.

Sponsored by André Malraux, Charles de Gaulle appointed him Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur and, at the request of Jack Lang, François Mitterand raised him to the rank of Officier. He was also appointed Officier de l’Ordre National du Mérite and Commandeur des Arts et des Lettres. In 1981 he received the UNESCO/CIM prize for music, and in 1987 UNESCO’s “Kathmandu” medal; he was an honorary member of the International Music Council, Honorary President of the Music Institutes in Berlin and Venice, and was promoted “Personality of the Year” in 1989. In 1991 he received the Cervo award for New Music and was appointed Member of the Indian National Academy of Music and Dance. In 1992 the Berlin Senate appointed him Professor Emeritus.

For the three record collections published on behalf of UNESCO, Alain Daniélou also received wide recognition, including many major disk awards.

As a result of his intervention, the music of eastern countries has taken its rightful place in the world’s musical culture. No longer is Ravi Shankar considered a folk singer, or the Gagaku a folk dance. Under his stimulus, music festivals now flourish all over the western world, presenting groups of musicians and dancers that attract ever-increasing audiences.

The Dagar concert at the Palace of Charlottenburg in 1964 was certainly the first step in this great adventure, and the idea of organising another to commemorate Alain Daniélou’s one-hundredth birthday is a major tribute to this visionary artist. The Dahlem Museum and Lars Christian Koch, Werner Durand and Amelia Cuni, and Peter Pannke, faithful and constant supporters of Daniélou’s work, deserve special thanks for this superb initiative.

Jacques Cloarec, Le Labyrinthe, 7 March 2007

MUSIQUE

Igor Wakhevitch has composed many works, several of which created for the Paris Opera, as well as other prestigious venues, such as the Fenicia in Venice, the Avignon Festival, the Festival of Shiraz-Persepolis (Iran), the Festival of Israel, and the National Centre of Performing Arts in India, working – among others – with the great American-Finnish choreographer Carolyn Carlson, the Israeli Rina Schenfeld; as also with Jean-Michel Jarre, signing a common score for symphony orchestra and recording tape. He is also the composer of “Etre Dieu”, an opera-poem in six parts by Salvador Dali, with Dali in person as the main performer, etc., without counting his considerable discography.

Igor Wakhevitch has composed many works, several of which created for the Paris Opera, as well as other prestigious venues, such as the Fenicia in Venice, the Avignon Festival, the Festival of Shiraz-Persepolis (Iran), the Festival of Israel, and the National Centre of Performing Arts in India, working – among others – with the great American-Finnish choreographer Carolyn Carlson, the Israeli Rina Schenfeld; as also with Jean-Michel Jarre, signing a common score for symphony orchestra and recording tape. He is also the composer of “Etre Dieu”, an opera-poem in six parts by Salvador Dali, with Dali in person as the main performer, etc., without counting his considerable discography.

Developed on an idea of Alain Daniélou’s and at his request, tuned according to his theory, the Semantic Daniélou is an electronic musical instrument conceived by Christian Braut, Michel Geiss and Philippe Monsire.

EN LIBRAIRIE

– Shiva and the Primordial Tradition

Inner Traditions International, Rochester, 2006.

Collection edited and presented by Jean-Louis Gabin, Translation by Kenneth F. Hurry.

From Publishers Weekly :

Better known in Europe than in the U.S., the late French intellectual Daniélou (1907–1994) forged an eclectic career spanning several disciplines, though he is best known for his work on Indian music and culture. As a convert to the Hindu denomination known as Shaivism (which worships the god Shiva as the supreme being), Daniélou broke the rule of objectivity in his study of Hinduism, which has hurt his standing in academia. For the spiritual seeker, however, his work is immensely valuable in bridging the gap between polytheistic Hinduism and Western monotheism. One theme overarches: monotheism is the soul of error, both in the West, which has been “hardly interested in anything but philosophies infected by this germ,” and in the East, where keepers of the “primordial” traditions have sought to ward it off. According to Daniélou, the healing power of Shaivism lies in opening oneself up to the divine spark in all things.

Better known in Europe than in the U.S., the late French intellectual Daniélou (1907–1994) forged an eclectic career spanning several disciplines, though he is best known for his work on Indian music and culture. As a convert to the Hindu denomination known as Shaivism (which worships the god Shiva as the supreme being), Daniélou broke the rule of objectivity in his study of Hinduism, which has hurt his standing in academia. For the spiritual seeker, however, his work is immensely valuable in bridging the gap between polytheistic Hinduism and Western monotheism. One theme overarches: monotheism is the soul of error, both in the West, which has been “hardly interested in anything but philosophies infected by this germ,” and in the East, where keepers of the “primordial” traditions have sought to ward it off. According to Daniélou, the healing power of Shaivism lies in opening oneself up to the divine spark in all things.

More specifically, he shows how the disciplines of yoga and tantric sex, familiar to many in the West, derive from this ancient tradition and are doorways into a deeper and more fulfilling life. As is clear from this slight volume, Daniélou’s Shaivic pluralism has much to say to our increasingly war-torn and materialistic culture and deserves a wide audience. (Jan.)

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

EXTRAITS

Sänger Müssen Zweimal Sterben, Eine Reise ins unerhörte Indien

(Singers must die twice, Trip in an undiscovered India)

Editions Malik Verlag 2006.

Benares, Winter 1973

In a hut under an enormous banyan, at the junction for Assi Ghat, a slender young man with curly hair, wearing merely a T-Shirt and a lungi, was serving tea. The flame beneath the little teapot had blackened with its smoke the frame and glass protecting the photograph. In the dim light, the profile of the face was indistinct. But I knew that I had already seen that face somewhere. When I asked Tschai Baba who was the man in the photo, he nodded his head towards the Ghat. “Shiva Sharan!” he grated through his vocal chords, dried up by the consumption of innumerable chillums. “That’s what we called him. In Europe his name was Alain Daniélou. But here he took the name “Shiva Sharan”, which means “Protected by Shiva”. He lived in Rewa Kothi, on the bank of the river, with Raymond Burnier, the photographer. Good man! He bought a house for his servant when he went back to Europe!”

In a hut under an enormous banyan, at the junction for Assi Ghat, a slender young man with curly hair, wearing merely a T-Shirt and a lungi, was serving tea. The flame beneath the little teapot had blackened with its smoke the frame and glass protecting the photograph. In the dim light, the profile of the face was indistinct. But I knew that I had already seen that face somewhere. When I asked Tschai Baba who was the man in the photo, he nodded his head towards the Ghat. “Shiva Sharan!” he grated through his vocal chords, dried up by the consumption of innumerable chillums. “That’s what we called him. In Europe his name was Alain Daniélou. But here he took the name “Shiva Sharan”, which means “Protected by Shiva”. He lived in Rewa Kothi, on the bank of the river, with Raymond Burnier, the photographer. Good man! He bought a house for his servant when he went back to Europe!”

Rewa Khoti was one of the most remarkable dwellings in the district, an imposing building with several storeys which, flanked by two round towers, rose like a fortress over the Ghat. Originally, it belonged to the Maharaja of Rewa. It had changed hands long before, but the first owners had become a legend on Assi Ghat.

I had seen Alain Daniélou’s name for the first time on that record that had drawn me to India. Everyone interested in Indian music knew Daniélou. He was the first European not only to take an interest in its theory, but also to have learned to play it. He was a very controversial figure among ethnomusicologists, and some of them thoroughly detested him. He had published one of the leading works on Indian music, but his interest went far beyond music itself. He was one of the last members of that now extinct race, the Universal Man. Rewa Kothi, where he lived for fifteen years, became a meeting point for artists and intellectuals, scholars and politicians. Eleanor Roosevelt was among the many visitors, like the photographer Cecil Beaton and Jean Renoir, the film director.

It may be that jealousy had something to do with the opposition that Daniélou encountered: his companion Raymond Burnier was one of the heirs of the Swiss Group Nestlé. Daniélou had been able to live in India for decades without restrictions of a material kind and thus devote himself to his studies without having to report to any university.

He had constantly refused a professorial chair and any submission to the western academic system. He reached the conclusion that Indian music was the equal of western music and that, like the latter, it had to be assessed on its own criteria. He found it contemptuous and wrong to consider Shastriya Sangit – that Indian music based on the Scriptures, the Shastras – from an ethnological point of view. Only someone who adopted the traditions of the country could understand Indian musicology. And that is what he did.

He was an extremely hard worker. He learned to play the Vina, translated texts, gathered an incredible number of manuscripts and published numerous books, not only on music, but also on many different subjects, ranging from the symbolism of the phallus to the comparison of the cults of Dionysos and Shiva.

He detested Nehru, considering him a product of western thought who owed his knowledge of Indian spirituality to works written in English. He held him responsible, together with Gandhi, for the bloody partition of India. In 1958, when India, having won its independence, took a direction of which he didn’t approve, he left the country definitively.

He saw signs that the ancient Indian culture he had known was about to disappear, just like traditional musical culture throughout the world. With the aid of UNESCO, the Ford Foundation and the Berlin Senate, he founded an Institute whose mission was to bring to Europe musicians of various cultures and to make their music known. For Daniélou, India represented the highest stage of such cultures. In his first record, he published recitations from Vedic texts that he had recorded at Benares. In the second, one hears the voices of Dhrupad singers, which I had followed back to India itself.

Zagarolo, Autumn 1992

It took twenty years before I again saw the face that I had glimpsed in the smoke-begrimed photo at the Assi “tearoom”. I visited Alain Daniélou at his enchanted villa on Colle Labirinto, a hillside south of Rome that in former times had served as a hospice for pilgrims going to the Temple of Fortune, in present-day Palestrina. I wanted to invite him to Berlin for a festival that aimed at informing the public about the path that Indian music had taken to the West. He had long retired from public life, but accepted nonetheless.

We were seated on the terrace in front of the house, viewing the autumnal landscape. The property was large, with a small wood and extensive meadows that came up to the well-kept swimming pool, surrounded by travertine paving and rose bushes. Over his shoulder I could see the hillside vineyard that gave him his own wine. The cook in livery – his thumb sticking out of a hole in his white glove – had served it gracefully during lunch. The wine had golden tints, the house was yellow, the sun enhanced the colours of the garden.

“Do you hear the birds?” he asked me. “You hear them a lot here. We don’t use any chemical fertilizer, so they come in great numbers. Snakes too. It is a privileged spot. Whoever comes feels at home.”

He was sitting in front of me, an old gentleman, long passed seventy. His face was thin, his blue eyes sparkling with mischief, his sparse grey hair carefully combed. In India, it is said that ears reveal musical talent. His were very large, with long lobes. A certain irony could be detected in his glance. A small golden winged phallus rested on his chest. I felt I was looking at a species of bird that was about to become extinct.

“Do you know what Sanskrit texts say about sacred geography?” he asked. “They say where you should live or not live. Benares, of course, is a perfect spot! People say that it has to do with the subterranean world and the stars. In the depths of the earth, below the city, runs an underground river; far above it is the Milky Way. They meet at Benares in the Ganges, which is why it’s the ideal place to live.” He added, with a mischievous chuckle, “And to die”.

I asked him why he had gone to Benares.

“I never had any intention of going there”, he replied. “I wasn’t one of those people that dream about mystical India. I was not at all prepared. It was a lucky chance, as I discovered on the spot.”

He had grown up in Brittany, the son of a man with anti-clerical ideas, who was a cabinet minister in several governments, and of a very Catholic mother, who founded a religious order. She was deeply upset on learning that Alain had taught himself to play the piano. His elder brother became a cardinal. Alain, the youngest, was the family’s enfant terrible. Too frail for a state education, he was taught by tutors. Then he went to Paris, learned composition, started painting, sang Schubert’s lieder and performed as a classical dancer. Very early on, he became acquainted with Igor Stravinsky, Jean Cocteau, Jean Marais and Maurice Sachs. In the Swiss Raymond Burnier, he found the love of his life. In 1932, they departed on a world discovery trip. They went to visit Zaher Shah, the son of the king of Afghanistan, with whom Alain was on friendly terms. Without permission, they penetrated Kafiristan, formerly forbidden to foreigners, before pursuing the path to India. At the open-air University of Shantiniketan, Daniélou was invited by Rabindranath Tagore, the Nobel Prize for literature, to take over the music department. But it was in Benares that he wanted to go.

“Almost immediately I started studying with a great Vina-player”, he told me. “From the start, I studied with a real master. That’s really the only way to learn Indian music!” he added emphatically.

In 1936, he and Raymond Burnier went to live at Rewa Kothi. Almost every day, Daniélou took the boat to the house of Shivendranath Basu, a zamindar who was a native of East Bengal and lived withdrawn from the world, spending his time playing the rudra-vina, Shiva’s instrument, which few musicians still play. The instrument has a very archaic look, but is perfect for meditation: two empty gourds connected by a bamboo tube, on which the frets are fixed. The player sits between the two gourds, enveloped by sound. This instrument is essentially conceived for the player himself, since the sound is directed towards the centre.

“My teacher”, continued Daniélou, “never played in public. He was a man of means and would have found it unworthy to steal work from professional musicians. He gave private concerts for his friends, but never played for money. He refused to give public concerts for ethical reasons!”

He laughed. “He was right! It is simultaneously a matter of caste and propriety. For me, he played every day, one raga after another. I asked him questions and he gave me explanations. I noted everything down. To begin with he was reluctant to give me lessons. In the end, he gave me a small vina, but refused to let me play in front of him. ‘You would only destroy my ear’, he said. ‘I couldn’t bear it.’ However, after some time, he began to praise me. ‘Alain is my best pupil’, he would say. But only when I wasn’t around!”

“When I left for India, I was at first considered to be a musicologist”, he went on. “That was totally different from being a musician oneself. Professional ethnomusicologists, straitjacketed by their European mentality, totally disapproved. ‘Daniélou? He can’t be a musicologist: he’s a musician!’ they would say. Playing music was deemed to be absolutely the opposite of scientific music study.”

With his slim fingers, the old man took a cigarette from his case and lit it. He had seemed tired, but remembering Benares brought his energy back.

“On arriving at Benares, I found myself at the centre of an ancient culture!” he said. “And I found that enormously interesting. If you want to be introduced to a society, you must first accept their rules. It’s a matter of manners and politeness. If people know that you’re not going to give them any unpleasant surprises, that you do your ritual ablutions in the Ganges, that you are not going to break any taboo, that you don’t touch what you have no right to touch, that you don’t do anything that might be deemed unseemly, then there’s no problem! The problem with most Europeans is that they’re not ready to abandon their habits and prejudices, and so they constantly offend the natives. If they’re absolutely sure that you can behave like a civilised person, there’s no problem! But for that, you must first put aside your ideas about what is good or bad, clean or dirty, moral or immoral.”

“I have never met with any conception of life more deeply reflected on than the Hindu. Their traditional conception, of course.” He raised his hands by way of protest. “I am absolutely allergic to modern India!” His brows puckered. “That horrible religious and moral sentimentalism, that never existed in ancient India.” He shook his head.

“According to the Hindu concept, the sole reason for existence lies in an appreciation of the Creator’s work. What a person doesn’t see doesn’t exist. Creation would not exist, if there were no one there to see it, appreciate it and try to comprehend it: that is what real religion is all about.”

I told him that at the beginning of the ’seventies, I had come upon his traces at Assi Ghat. The few westerners that used to study music at Benares had become a great international crowd since he had left. Most of them were Americans: their universities were generous in providing students with grants. They were followed by the English, French, Italians, Israelis, and a scattering of Germans. Some of the German music students had to do without grants and, in Germany, the professor I had got to know took care that none of his young ethnomusicologists should think of touching a sitar or tabla, whether at Assi Ghat or elsewhere.

“People of that sort have the mentality of slaves”, he remarked. “They sell their bodies and work to organisations in which they are not interested. Solely for the purpose of getting a pension in their old age.” His smile was again half-ironic, halfdisenchanted. “What a sad view of life they have!”

He was silent for a moment, took a cigarette from his case and lit it. “I’ve never been serious”, he said finally. “I feel that it’s an advantage not to be taken too seriously by the establishment, to remain outside and consequently to be free.”

“I believe you’d like to go for a walk in the park”, he added, bringing our conversation to a close. “The apples are ripe. The fruit you gather yourself from the tree always tastes better than what you are served on a plate!” Translated from the German by Claude Franco Berlin, February 2007

Translated from the German by Claude Franco, Berlin, February 2007

CLIN D’OEIL

We shall take advantage of the imminent appearance of the Spanish edition of The Way to the Labyrinth, by the publishers Kairos of Barcelona, to take a glance at what Pierre Gaxotte wrote in the following article for Le Figaro when the French edition first came out.

« The Labyrinth:

The hill of the Labyrinth lies between Rome and Palestrina. It is there, in an enlarged and modernised peasants’ house, that Alain Daniélou now lives, a man from France who best knows India. The son of a cabinet minister and brother of a cardinal, he spent part of his schooling in America and on his return from one of his trips, he got to know, in the south of France, Raymond Burnier, an extremely rich young Swiss, who became the companion both of his life and his travels.

In actual fact, Alain Daniélou travelled all over the world, or nearly. He met all the celebrities, some of whom became his friends. To start with, accompanied by Raymond, we find him in North Africa, in the Middle East, in China and Japan. But it was in India that he found a second home. Tagore offered him the directorship of his school of music, Alain refused. He learned Hindi, which he writes and speaks as his own mother-tongue, and also Sanskrit following the traditional methods.

For lodgings, the two friends found at Benares, on the bank of the Ganges, a very beautiful mansion belonging to the Maharajah of Rewa, a small state in central India. It cost them about one hundred dollars a month. They lived there for fifteen years, surrounded by all kinds of animals, including a python – which bit Raymond close to his eye -, a white parrot that warned them of earthquakes, martens that would have been unbearable if a small monkey had not been in charge of their education, generously distributing smacks, and lastly a small bottle-fed doe that a wolf had tried to seize. Alain rescued her by pulling the wolf’s tail, so humiliating him that he went away and never came back.

One of the pleasures of this book is the simple, alert manner in which it is written. Mr. Daniélou finds the picturesque without having to look for it. His portrayals are delicately done, with exceptional penetration. Musicians occupy an important place, because Daniélou recorded untiringly for the gramophone, compiling a kind of encyclopaedia of Asiatic music, while Raymond, who had had a caravan brought from the United States, visited the lesser known temples and photographed their sculptures, a valuable collection that had never been made before, which an exhibition at the Bérès bookstore made known to Paris as soon as it was set up. In the meantime, the two friends converted to Buddhism. The ceremony was performed scrupulously. Raymond ended up getting married. He married the daughter of the chairman of the Madras theosophical society, a dancer and actress, who can be seen in Renoir’s film The River (Le Fleuve). The marriage didn’t last. Raymond died suddenly, perhaps by poison.

Portraits abound in this autobiography: tradesmen, artisans, servants, politicians. The very ones our newspapers treat as great men. Some lowering of tone is needed: Gandhi, writes Alain, I found totally repugnant… This small thin man, a puritan, “led a life of extreme luxury, travelling in a third-class carriage that had been remodelled for him; he lived surrounded by a court of young girls, charged in turn with massaging his legs. Like Nehru, he had studied law in London and didn’t know much about the hierarchical world of the Hindus. Thus it was these three anglicised lawyers that London put in charge of India’s independence and partition: Gandhi, Nehru, Jinnah, the Muslim leader. And it all began with massacres.

Mr. Daniélou, having now returned to Europe, is at the age of remembering. We have much to learn from him.” »

Pierre Gaxotte, le Figaro, January 1982.

THÈSE

– Inde- France (1870-1962) : Enjeux Culturels

Institut Français de Pondichéry – Centre de Sciences Humaines

Collection Sciences Sociales n°12 par Samuel Berthet :

The country controlling India is the most powerful in the world, Napoleon said. As soon as the end of the Eighteenth century, Indian culture impulses a new trend inn French humanism, notably with Anquetil-Duperron. In the early Nineteenth, the elites of the sub-continent ruled by the British start to conceive the French culture as an instrumental factor in modernity making. From the 1870 onwards, the attempts of the British authorities to contain their emancipation increased the interest of the Indian elites in French language and culture. If this effort towards emancipation from the British rule takes the Indian elite closer to the century of the revolution and of the lingua franca of the cosmopolitan elite, the Third republic leads irrevocably the French nation towards the colonial path. Political, economic but also cultural dynamics will deeply be affected by this choice. Solidarity with the British ally will prohibit France to start playing the role of privileged partner wished by the Indian elite. By the time of independence and in the following years, the perception of India of the relations between the two countries will be considerably altered by the French colonial experiment of the past decades.

The country controlling India is the most powerful in the world, Napoleon said. As soon as the end of the Eighteenth century, Indian culture impulses a new trend inn French humanism, notably with Anquetil-Duperron. In the early Nineteenth, the elites of the sub-continent ruled by the British start to conceive the French culture as an instrumental factor in modernity making. From the 1870 onwards, the attempts of the British authorities to contain their emancipation increased the interest of the Indian elites in French language and culture. If this effort towards emancipation from the British rule takes the Indian elite closer to the century of the revolution and of the lingua franca of the cosmopolitan elite, the Third republic leads irrevocably the French nation towards the colonial path. Political, economic but also cultural dynamics will deeply be affected by this choice. Solidarity with the British ally will prohibit France to start playing the role of privileged partner wished by the Indian elite. By the time of independence and in the following years, the perception of India of the relations between the two countries will be considerably altered by the French colonial experiment of the past decades.

Samuel Berthet, historian and researcher, specialist in contemporary India. Studied in Delhi University and visiting lecturer in Visva Bharati and Jawaharlal Nehru. Completed his Ph.D in the University of Nantes under the supervision of professor Jacques Weber. He is affiliated to the Centre de Sciences Humaines (New Delhi) and research coordinator of the European project, Europe-India Maritime history.